Insights: The challenges of tracking migratory birds

The challenges of tracking migratory birds like the Swift Parrot and Regent Honeyeater

World Migratory Bird Day (WMBD) is all about celebrating the world’s wonderful migratory birds. To help raise awareness of the threats faced by migratory birds, and the urgent need to conserve their habitats, we’re taking a look at two of Australia’s most prominent endangered migratory birds: the Swift Parrot and Regent Honeyeater.

We’re also stepping back in time to reflect on how the Swift Parrot inspired our founder and CEO, Dr Debbie Saunders to launch Wildlife Drones back in 2016.

Thousands of bird species migrate every year

Chances are, one of the first things that spring to mind when you hear the term ‘migratory bird’ is geese flying south for the winter. But geese, and other large northern hemisphere birds, aren’t the only ones that move to warmer climes in search of food and nesting sites during winter.

The Arctic Tern journeys 25,000 miles—or just over 40,000 kilometres—each year between its Arctic breeding ground and its summer home in the Antarctic, while the Eastern Curlew travels from Siberia and northern Mongolia, to spend the summer in Australia’s coastal wetlands.

While Australia hosts 37 species of migratory shorebirds each year in addition, to the species that migrate entirely within the country, more than 350 North American birds are long-distance migrants, splitting their time between Canada, the United States and Mexico.

Flyway conservation is crucial for migratory birds’ survival

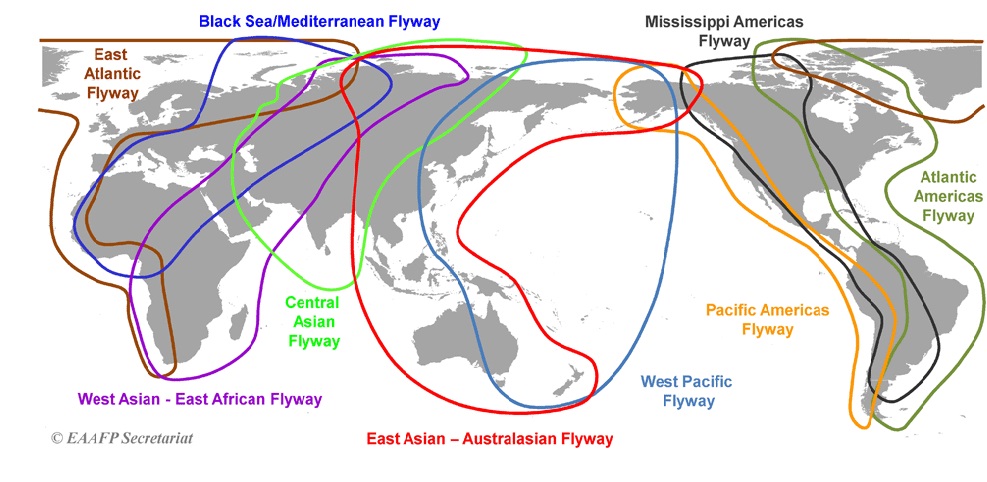

Migratory birds travel along flight paths known as ‘flyways.’ There are nine major flyways around the world, including the:

- East-Asian Australasian Flyway, which spans 22 countries between the Arctic Circle in Russia and Alaska, through East and South-east Asia, to Australia and New Zealand.

- Pacific Flyway, which is a major north-south flyway stretching from Alaska to Patagonia.

- Central Asian Flyway, which covers large areas of Eurasia from between the Arctic and Indian Oceans.

Maintaining migratory bird habitats along flyways is critical for protecting endangered species. Birds typically visit the same areas along these routes year after year, and depend on being able to rest and access food along the way. Accordingly, flyway habitat protection requires a coordinated international approach that recognises the importance of conserving land along the entire length of the flyway.

Numerous multilateral agreements are crucial to these conservation efforts, including:

- The Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918, which was passed to protect birds from over-hunting.

- The Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals, which is the only global convention to conserve migratory species.

- Numerous bilateral agreements, such as the China-Australia Migratory Bird Agreement, which focus on conserving habitat, preventing take or trade of migratory birds, and facilitating information exchange.

The Swift Parrot and Regent Honeyeater are two of Australia’s most well-known migratory birds

As well as being the summer home of at least two million migratory waterbirds each year, Australia is home to many native birds that migrate within Australia.

Bright green with small crimson patches around its beak, the Swift Parrot (Lathamus discolour) is one of Australia’s most well-known migratory birds. It breeds in Tasmania during spring and summer, before migrating north to the south-eastern Australian mainland in autumn and winter, where it feeds on flowering gums and lerp.

Like the Swift Parrot, the beautifully black and yellow patterned Regent Honeyeater (Anthochaera Phrygia) migrates within eastern Australia according to food availability, returning to traditional breeding grounds in Victoria (Chiltern-Albury) and NSW (Capertee Valley and Bundarra-Barraba) each year. Regent Honeyeater banding studies have shown that the birds can travel up to several hundred kilometres, and Swift Parrots are known to travel more than 1000km north from their breeding range in search of winter nectar sources.

Due to habitat fragmentation, climate change (including more frequent droughts), predation and competition from other species such as sugar gliders and noisy miners, both the Swift Parrot and Regent Honeyeater are critically endangered. There are as few as 300 swift parrots and between 800 and 1,500 regent honeyeaters left in the wild.

You can help save these species by participating in Swift Parrot and Regent Honeyeater surveys this May

For more than 25 years, BirdLife Australia has run Swift Parrot and Regent Honeyeater surveys. This important citizen science program has helped gather population monitoring data to better understand the birds’ distribution across the mainland. With climate change altering the distribution of these species and disrupting seasonal eucalyptus flowering patterns, it’s more important than ever that we build a clear picture of the birds’ movements.

In 2022, the first round of surveys will run throughout the month of May. There are approximately 2,000 monitoring sites across Victoria, NSW and the ACT where you can participate by undertaking a 5 minute/50-metre radius search for Swift Parrots and Regent Honeyeaters. You will also be asked to record counts for all other bird species, and to estimate the availability of nectar and water.

The challenges of tracking Swift Parrots inspired Dr Debbie Saunders to start Wildlife Drones

For over 20 years, Dr Debbie Saunders has worked as an ecologist studying the movements of small migratory birds, including the Swift Parrot. Like many small animals, Swift Parrots can only be tracked with tiny, very high frequency (VHF) radio tags. As a result, researchers have traditionally depended on time-consuming and labour-intensive manual tracking methods to search for the birds on foot, one at a time. Because the Swift Parrot is a highly mobile creature, tracking them like this is a near-impossible feat.

To overcome these challenges, and enable scientists to build a clear picture of birds’ migratory patterns, Debbie led a research team to develop the world’s first drone-based radio-tracking system. Since then, Wildlife Drones has revolutionised the wildlife monitoring industry and is paving the way for more sustainable and regenerative conservation management.

Since then we have worked with environmental consultants in the United States to track the migration patterns of endangered microbats, scientists in Australia to track migratory Orange-bellied parrots, and conservationists in New Zealand to monitor the critically endangered Kakapo to name just a few.

With our innovative technology, wildlife biologists can collect more data, more often, and with less effort by:

- Tracking up to 40 animals at the same time;

- Removing the need to traverse challenging landscapes; and

- Enabling real-time data analysis and mapping.

Get in touch today to find out how Wildlife Drones can help you overcome the challenges of tracking migratory species.